Dear Stranger is a film that was woven across national borders.

Items from Yohji Yamamoto POUR HOMME appear as the wardrobe for the protagonist Kenji, becoming a key supportive element in the story crafted by director Tetsuya Mariko. To

To commemorate the film’s release, a special collaboration with WILDSIDE YOHJI YAMAMOTO has also been launched.

In this article, we explore the meaning that the act of “wearing black” brought to the film, drawing form the words of Director Mariko and a behind-the-scenes look at the production.

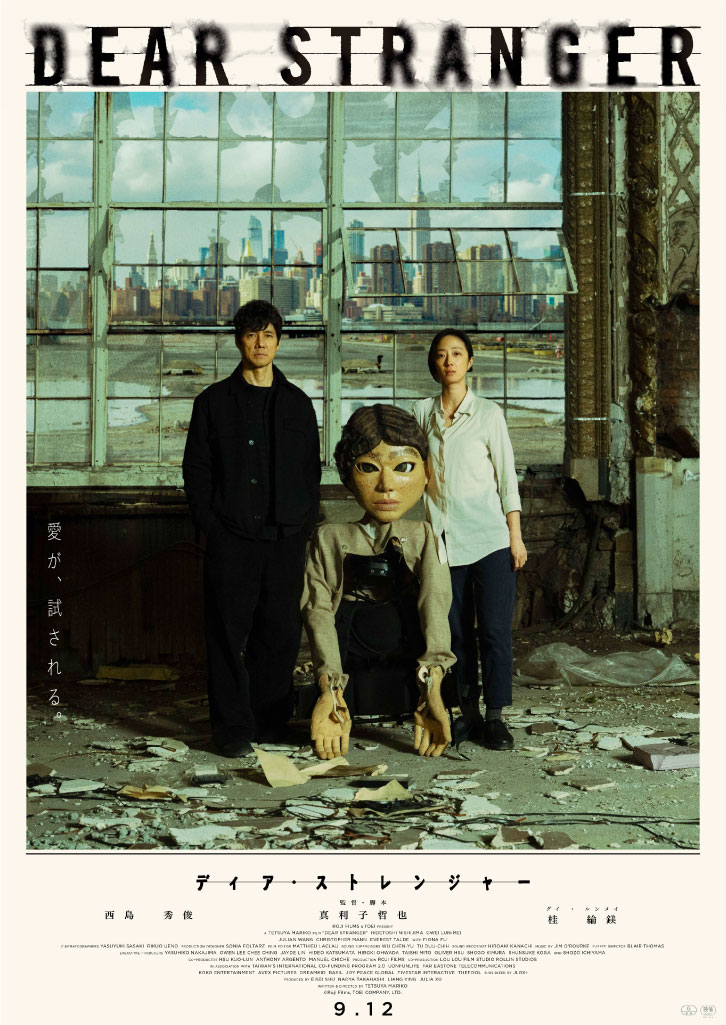

Film “Dear Stranger”

The film will release in Japan on Friday, September 12.

This is a deeply human suspense film, and a co-production between Japan, Taiwan, and the U.S.A.

Kenji (Hidetoshi Nishijima) is a Japanese man living in New York with his Asian American wife Jane (Gwei Lun-Mei). The pair lead lives with little room to spare for themselves, overwhelmed as they are with work, parenting, and elder care. One day, their young son is kidnapped in an incident that escalates into a murder investigation. As they are buffeted by tragedy, their previously

unspoken feelings and secrets are laid bare, deepening the rift between them.

Can the couple revive the “happy family” once strived for?

Interview with Director Tetsuya Mariko

-What was the filming process like, set in New York and shot with a multinational team from Japan, Taiwan, and the U.S.?

We were filming in New York, USA, in a land so unlike Japan. We had to build our staff and crew from the ground up, and though a few staff members came with me from Japan, we first had to learn American filmmaking and communication styles from zero.

It was crucial for us to work together as a single unit, so I made sure we dedicated significant time to understanding our new partners and our new environment.

Having actually done it now, I feel the methods of filming in Japan and the U.S. are indeed different, but the desire to create something great is universal.

One major difference is that American film crews have a mindset of "at first, enjoy." Integrating filmmaking into their lives is important, so they focus on how to do their level best within a set framework, one of which were their labor hours. Because of this, and the language barrier, we prepared more detailed shot lists than we would have in Japan, and tried our best to communicate meticulously, so they were ready and willing to listen too.

While we didn't have a large Japanese contingent, I was able to achieve what we wanted through trial and error.

I think we were able to output our best work in the limited time we had available.

-What are your own thoughts and feelings about the title, Dear Stranger?

We used a different working title throughout the shoot. It was only when the film was nearly complete that the staff and I discussed it and settled on Dear Stranger.

I like it, because this is ultimately a film about family and about love. The title implies that even in a marriage, where you have communicated for years and are each other's most trusted companion, you are still, in a sense, strangers. It has the impression of asking whether you can love your neighbor as you love yourself.

It’s two simple English words, and I feel it’s a fitting title for this film.

-What was the reason or intent behind incorporating elements like "ruins" and "puppetry" into the story?

While developing the script, I started by thinking about the professions of the main characters, Kenji and Jane. A major factor was my own fascination with certain American landscapes. Ultimately, their work of researching "ruins" and working with "puppets" became incredibly important to the story. There wasn't a strictly logical reason for it. It felt more like everything connected naturally.

Whether it was the “ruins” or the “puppets”, these were the things the characters are drawn to, and because their passion is so strong, they clash over trivial matters when they are together. Even as a family, they are still individuals. I felt the characterizations of a scholar who researches “ruins” and a “puppeteer”, in other words an artist, were vital, and that's why I chose them.

-The lead actor, Mr. Nishijima, has often said he "accepted the offer to appear in this film because of Director Mariko." How do you feel about that as the director?

It’s incredibly humbling. He's an actor I've been watching since the 90s, so I'm just so happy that we had the chance to work together at this moment. On a project where so much was riding on, especially.

I’m sure it was difficult for Mr. Nishijima to work in a film set outside Japan, but he was incredibly dedicated and practiced his English constantly. Although he never said it to me directly, I’m sure he felt some constraints in his performance. But he found a way to work within those limitations to create the character. So he was a truly dependable person, and that feeling spread not only to me but to the rest of the cast and crew. It really led to a strong sense of trust between everyone.

©Roji Films, TOEI COMPANY, LTD.

©Roji Films, TOEI COMPANY, LTD.

-You depict a married couple who are not native English speakers. What was your intention with this dynamic?

This is something I saw while I was researching. I spoke with people in international marriages, and I don't believe the language barrier itself is the single greatest obstacle. Slight misalignments in what you truly want to say occur even when you speak the same language. I imagine that for two people who grew up in separate linguistic environments and then have to communicate in English, the stress of casual communication might even be heightened.

Even between two Japanese people, no matter how often they talk with each other, small misalignments can appear due to differences in gender norms, or differences in personal values in general. I wanted to depict these kinds of everyday miscommunications. When thinking about how to make the film relatable for the audience, setting it in America with two people from different countries speaking English felt like a choice that was consistent with these themes,

-From a directorial point of view, what role do "attire" and "clothing" play in telling a story?

The protagonist, Kenji, is in the architecture department researching ruins. During my research, I interviewed multiple architecture professors but noticed that they always wore black. When I searched online, most of the architects in photos of lectures I saw were also wearing black. Apparently, it's some sort of unwritten rule. During pre-production, one of the professors I met with handed me a book titled WHY DO ARCHITECTS WEAR BLACK? In it, famous architects from around the world answered that very question, and I found much of it relatable.

There were many different answers, but the gist was that there is no actual rule about wearing black, but it is a philosophy, an intuition, a uniform for those who work behind the scenes. In other words, wearing black in itself is also a form of expression. Sometimes black is worn to act as a Kuroko, a stagehand in Japanese theater whose black clothes signal their behind-the-scenes nature. While style is always freedom, I believe that is precisely why clothing in a film is a crucial motif that influences the presence of the actor who wears it.

That single piece of clothing is a dialogue between the director and the actor, it’s a part of the film's image, and it’s a message to the audience. In the end, it’s the communication and collaboration leading up to the final decision of that one piece that is both enjoyable and important.

-Do you have any comments on the collaboration between the film Dear Stranger and Yohji Yamamoto?

The film's costume designer, Lizzie Donelan, and I decided early on that Kenji's clothes would be Yohji Yamamoto. This was essential for us, coming from different cultures, to share a common image of Kenji. When I saw Mr. Nishijima actually wearing Yohji Yamamoto, I was certain we had made the right choice. The resulting film, both in its ideas and its visuals, turned out to be very cool, I think. (laughs)

I am incredibly humbled and honored that the team at Yohji Yamamoto watched the film and that it led to this collaboration, which was completely unexpected. This is a gift born from film and fashion, and a beautiful and welcome reward for the challenges we took on with Dear Stranger. I truly hope that everyone who sees the film will get a chance to experience these items.

©Roji Films, TOEI COMPANY, LTD.

©Roji Films, TOEI COMPANY, LTD.

WILDSIDE YOHJI YAMAMOTO × Film Dear Stranger Collaboration Items – Available Here

TETSUYA MARIKO

Born in Tokyo in 1981.

While studying at Hosei University, he directed an independent short film shot on 8mm film that attracted attention both in Japan and abroad.

His graduation project at Tokyo University of the Arts, Yellow Kid (2009), received critical acclaim internationally and, in a rare case for a student film, was released theatrically.

After directing medium-length works such as NINIFUNI (2011) and FUN FAIR (2012), his feature film Destruction Babies (2016) was released in theaters and went on to win numerous awards at home and overseas, including the Best Emerging Director Award at the 69th Locarno International Film Festival.

His 2019 feature Miyamoto (From Miyamoto to You) earned him the Best Director Award at the 32nd Nikkan Sports Film Awards (Ishihara Yujiro Award) and the Best Director Award at the 62nd Blue Ribbon Awards.

©Roji Films, TOEI COMPANY, LTD.

©Roji Films, TOEI COMPANY, LTD.